Our Animated Anecdotes this week is from the brilliant Dr Kathleen Waller of The Matterhorn Substack Dr Kathleen offers incredible insights to readers, writers, film buffs and all curious thinkers. The Matterhorn Substack offers a wide range for the curious mind with well-written, informative pieces to expand your horizons.

Dr Kathleen also writes a great Substack, Yoga Culture that explores the inside of yoga culture mind widening insights.

Animated Anecdote

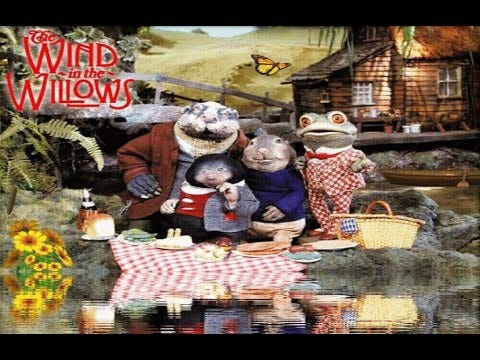

As a child in the 1980s in America, my favourite time in front of the television was when a special import from the UK arrived in our living room. Since my parents and grandmother loved the perhaps more subtle and darker British fare, we were even allowed to watch shows like murder mysteries that were sure to give us nightmares. One wouldn’t expect anthropomorphic animation to fall into this adult category, but The Wind in the Willows was special because it spoke to children as if we were adults.

In rewatching several of the episodes recently with my nearly-five-year-old son, I was taken aback at first. Drunk characters, prison escape, car crashes, guns, home loss…and many adult conversations confused us both. “Where are the kids and where are the girls?” he asked. It’s an upper middle class male society that is depicted, but one I see as synecdoche; that is, their small world stands for us all.

In fact, I think we should speak to children more like adults on a regular basis. I learned over the years as a teacher, most recently with some young ones in the art classroom, that they understand a lot more than one might assume, and they respect adults who afford them that maturity. However, there are certainly limits to this mindset. Framing and discussing these issues of the adult world are at the heart of it.

I encountered the book The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame (1908) a year or so before viewing the 1980s stop-motion television series, taking turns reading it aloud with my mother. I recall feeling energized by the strange journeys we discussed. Toad’s downfall is driven by a kind of mania and addiction (to cars) but one that his friends see as sympathetic. Despite his continuous mistakes, they help him. It doesn’t matter that Mole lives in a dirt hole on Toad’s land and Toad lives in a mansion; they are friends. Friends help one another. If fact, in helping, Mole is able to find his courage and happily returns to his once ravaged home to rebuild in solitary bliss.

I also recently rewatched the 1996 film – Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride, from Terry Jones of Monty Python fame, which my British husband describes as ‘very British’, filled with ‘national treasures’ like Steve Coogan and Michael Palin. The pastoral, character humility, and British humo(u)r make it ‘very British’. The way the actors are only loosely costumed as animals – a tinge of green makeup on Toad, a long tail and several whiskers on Rat – make the film look like more of a play and remind us that adults are performing an act, though it’s unclear if it is for children or themselves (both the actors in the process of making the film and adults in general). I was completely enthralled by it yet again. As much as the unexpected bizarreness of toads flying planes and an unruly rabbit-juried courtroom, it’s the conversations for me. The animals talk clearly about their feelings of isolation, homesickness, friendship, and more. Ordinary things that are the heart of being human.

The animal-domestic

One such focus on humanity in the television series (as well as the 1996 film) is on the domestic space of each animal, both aesthetically pleasing and personalized. These cozy interiors offer protection from weasels and humans as well as allowing the animal to use items as symbols of their character and desire to be surrounded by fine things, even if home is an underground hole made of dirt (in the case of Mole). Welsh dressers with individualized plates, trophies, unique clocks, small statues, sporting equipment, instruments bearing sheet music, and refined drinking vessels adorn and inhabit these spaces.

Several academic articles have focused on this domestic space in the series and original book. In “Style and the Mole: Domestic Aesthetics in The Wind in the Willows,” Seth Lerer focuses on Grahame’s original use of these spaces in Victorian terms and the way they evoke a Ruskin-like quality as well as showcase the “spiritual” side of items passed down through generations in a home. In “’Chops, . . . Cheese, New Bread, Great Swills of Beer’: Food and Home in Kenneth Grahame's The Wind in the Willows,” C.W. Sullivan III discusses the way home is “a place in which one stays complete or to which one returns for fulfillment or completion.”

As children, we are enamored of types of homes, playing with dollhouses or treehouses and making abodes of sandcastles or makeshift tents. This show gave my imagination ideas of spaces to inhabit, to play with real life and my own identity. Eventually, I wrote my PhD dissertation on the way filmic apartment spaces allow immigrants to form relational spaces with their host country. I love the way home tells a story.

Stop-motion anthropomorphic aesthetic

I’ve always been a fan of the technique of stop-motion. It tends to slow down the actions of the characters, allowing us to dwell on their movements and conversation. In this case, The Wind and the Willows included many tiny details of costume, mise-en-scene, and movement to create a vivid world. Its dimensionality creates a parallel-universe-like space we can imagine jumping into.

The pastoral here features. Each start to an episode depicted the viewer entering an old book and encountering the seasons of change through vegetation, precipitation, and more. Both large and small details give layers to this text; it is this texture of life that I recall immersing myself in as a child. Compare even the movement of the eyelids and front limbs of the different animals, and one can see personality through this 3D creation. The aesthetic itself was a mystery to ponder.

The technique of animals-as-people additionally unguards us to the deeper ideas the TV show helps us to encounter as an extension of the original book. These cute, harmless creatures are inviting. They at first appear like our playthings, whether you called them ‘stuffed animals’ or ‘teddies’ as a child, they spoke to each other and accompanied us on journeys and through times of emotional difficulty, when we may not have known what language could describe our feelings. But these animals do have words. They are empathetic and kind or naughty and challenging. We learn about the real world through them and the metaphors they represent.

Go back to this series if you dare discover the deep thoughts you may have experienced as a child. Maybe I was just an old soul. Or, maybe the ability to delight in these small things – movements and conversations – is something I’ve tried desperately to hold onto when life sometimes feels too big. As Rat says to Mole: “Believe me, my young friend, there is nothing – absolutely nothing – half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats.”

Want a little more? If this has whetted your appetite, why not watch these videos?

This was a classic & Dr Waller wrote such a heart warming piece.

Brilliant examination of an old classic! And who knew there were so many academic articles about it?! I agree 100% about speaking to children more like adults, and think this shows a two-way respect. Something that rankles me no end is when I hear adults speak down to children (of any age) as though their opinions are not valid. I love that you and your family watched British imports together! Some of my fondest memories are of watching (some of them wholly unsuitable, now I think of them) US imports with my mum.